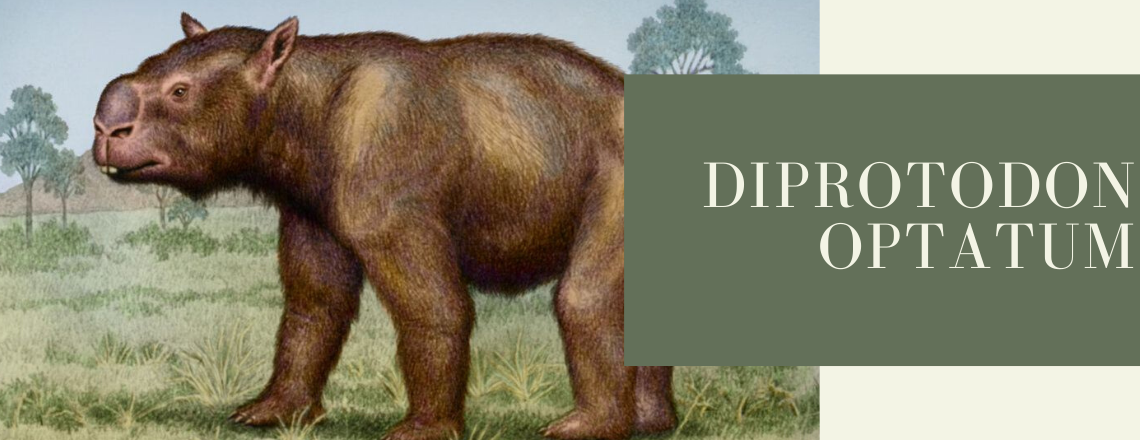

Megafauna – Diprotodon Optatum

It is believed that megafauna initially came into existence in response to glacial conditions. The extinction of megafauna around the world was probably due to environmental and ecological factors. It was almost completed by the end of the last ice age.

The massive Diprotodon optatum, from the Pleistocene of Australia, was the largest marsupial known and the last of the extinct, herbivorous diprotodontids. Diprotodon was the first fossil mammal named from Australia (Owen 1838) and one of the most well-known of the megafauna. It was widespread across Australia when the first indigenous people arrived, co-existing with them for thousands of years before becoming extinct about 25,000 years ago.

These larger than life creatures weighed in between one and two tonnes, stood 2 metres tall and measured 3 metres long. They were a flat-footed creature but able to walk (much like a wombat) at a pace of some 5 km an hour.

Like many large living herbivores, Diprotodon was a heavily built, large-bellied quadruped. Its oversized skull, like those of other diprotodontids, was lightweight and filled with numerous air spaces. Some scientists believe that Diprotodon may have had a short trunk because of the retracted position of the nasal bones (bones of the snout).

Diprotodon is known from many sites across Australia, including the Darling Downs in south eastern Queensland; Wellington Caves, Tambar Springs and Cuddie Springs in New South Wales; Bacchus Marsh in Victoria; and Lake Callabonna, Naracoorte Caves and Burra in South Australia. Diprotodon is not known from New Guinea, southwestern Western Australia, the Northern Territory or Tasmania (although it was present on King Island).

The discovery of fossils in the Burra area, has excited the most seasoned palaeontologists, describing Burra’s backyard as one of the richer megafauna sites in Australia. The fossilised remains of extinct marsupials were first reported from a site along Baldina Creek in 1889. Amandus Zeitz of the SA Museum visited the area and collected a partial skeleton of Diprotodon australis which at the time was the most complete specimen known from South Australia predating the finds at Lake Callabonna.

Subsequent prospecting further downstream revealed many small outcrops of weathered bone and fragments of the distinctive Diprotodon tooth enamel leading ultimately to the discovery of articulated skeletal remains of Diprotodon and a Tasmanian tiger, Thylacinus.

The Baldina and Burra Creek fossils occur in fine grained siltstones and mudstones. Bones excavated from deep below the weathered surface sediments, are well preserved. Specimens are difficult to locate and extract.

The oldest fossils of the genus Diprotodon come from late Pliocene deposits at Lake Kanunka, South Australia and Fisherman’s Cliff, New South Wales. Diprotodon optatum is known from the Pleistocene, becoming extinct at about 25,000 years ago. Complete skulls and skeletons as well as hair and foot impressions have been found. There is also a trackway preserved at Lake Callabonna.

The most complete specimen is the skeleton of a very large individual found at Tambar Springs in NSW and excavated by Australian Museum palaeontologists. It is now part of the Australian Museum fossil collection and is on display at the Coonabarabran Visitor Centre in central New South Wales. On one rib, there is a small, square hole tentatively identified as having been made by a spear while the bone was still fresh. This is one of the few pieces of evidence that humans may have hunted Diprotodon.

Excavations require skilled palaeontologists with years of training and extensive experience. It is illegal to remove fossilised remains from their resting place. Severe penalties apply to persons who attempt to do so.